Yeshayahu, Hoshea, and Mikha in the Time of Chizkiyahu (8)

The rise of Sancheriv: Preparing for the revolt in Jerusalem (705 B.C.E.)

The death of Sargon (and, especially, the sensation over the disappearance of his body in battle) fanned the flames of conflict which had died down throughout the empire under his ruthless reign. In Egypt, Shebitku, the uncle of crown prince Taharqa (who was too young to reign), became king. Unlike his older brother, Piye, who had maintained a cautious relationship – perhaps even friendly ties – with Sargon (and had handed Yamani of Ashdod over to him, in chains), Shebitku decided to seize the changeover of power in Assyria as an opportunity to shore up the power of his own kingdom by organizing the nations of the region into a rebellion. He viewed Chizkiyahu, king of Yehuda, as his chief partner. Chizkiyahu’s regional status was at its peak, and the diplomatic ties that he had created over the course of a decade gave him the confidence to officially declare his support for and partnership in the revolt.

The revolt seems to have begun with the Philistine city of Ekron. (Tel Ekron was identified to the south of Nachal Sorek, and has been excavated.) Records to this effect can be found in Sefer Melakhim as well as in Sancheriv’s inscription. According to Melakhim II (18:7-8), Chizkiyahu “rebelled against the king of Assyria, and did not serve him” (i.e., stopped paying tribute); furthermore, “He smote the Philistines as far as Gaza and its borders, from the tower of the watchmen to the fortified city.” According to Sancheriv’s inscription, Chizkiyahu managed to stage a revolution in Ekron, and its inhabitants handed over Padi, their king, who was loyal to Assyria:

And the people of Ekron, who overthrew their king, who was bound by oath and curse to Assyria, handed him over to Chizkiyahu of Yehuda. And he placed him in prison, like an enemy.[1]

Divrei Ha-yamim also contains, as an aside, possible evidence of military mobilization far from Jerusalem – on the border between Gaza and the central Negev. The text discusses an incident at Mount Se’ir, to the south of the biblical Negev (today – the Negev mountains and the approach to Sinai), involving nomadic shepherds from the tribe of Shimon:

These mentioned by name were princes in their families, and their fathers’ houses increased greatly.

And they went to the entrance of Gedor, all the way to the east side of the valley, to seek pasture for their flocks.

And they found pasture that was fat and good, and the land was wide, and quiet, and peaceable, for of Cham were those who had dwelled there previously.

And these written by name came in the days of Chizkiyahu, king of Yehuda, and smote their tents, and the Meunim who were found there, and destroyed them utterly until this day, and dwelled in their stead, because there was pasture there for their flocks. And some of them, of the sons of Shimon, five hundred men, went to Mount Se’ir, with Pelatia and Ne’aria and Refaya and Uziel, the sons of Yish’i, as their captains. And they smote the remnant of the Amalekites that escaped, and dwelled there to this day. (Divrei Ha-yamim I 4:38-43)

The tranquility enjoyed by the descendants of Cham, and by the “remnant of the Amalekites that escaped” who were their neighbors, was disturbed by a group of men who are “written by name” in “the days of Chizkiyahu.” According to some contemporary scholars, these were men conscripted into Chizkiyahu’s army, who established military outposts in the south and throughout the mountain and wilderness region south of Gaza, all the way to Mount Se’ir.[2]

Taking into account Sargon’s military and economic efforts against the nomadic tribes on the Egyptian border (716 B.C.E.), even prior to the revolts in Ashdod, we are led to conclude that Chizkiyahu encouraged the tribes of Israel in the south – and especially the nomads of the tribe of Shimon – to seize control in the area in order to replace Assyrian rule with a Jewish presence (with Egyptian support).

All of the above indicates that Chizkiyahu was at the forefront of the preparations for revolt, and was very close to the border of Egypt and the Philistine coastal strip. All this could happen only if his source of support was the king of Egypt, who fanned the flames with a view to expelling the Assyrian conquerors from the land.

Fortification of Jerusalem

Chizkiyahu’s main preparations for war were made in Jerusalem itself. His major project was connected to the city’s waterworks, based on his understanding that this was the city’s weak spot. Demonstrating engineering skill far ahead of his time, he prepared the infrastructure to stand up to a siege.

Sefer Melakhim makes only passing reference to this tremendous initiative; Divrei Ha-yamim expands at slightly greater length:

And when Chizkiyahu saw that Sancheriv had come, and that he intended to fight against Jerusalem,

He took counsel with his princes and his mighty men to stop the waters of the fountains which were outside of the city, and they helped him.

So a great throng gathered and they stopped all the fountains, and the brook that flowed through the midst of the land, saying: Why should the kings of Assyria come, and find much water? (Divrei Ha-yamim II 32:2-4)

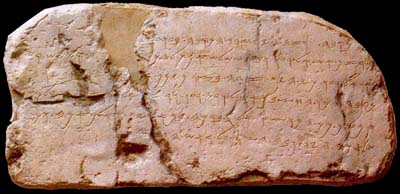

A Hebrew inscription that was found engraved in the rock near the end of the tunnel, known as the “Shiloach inscription,”[3] provides testimony to this exceptional engineering feat. It records the joyful meeting of the two teams of diggers, who had started at opposite ends of the tunnel, with “a hundred cubits the height of the rock over the heads of the diggers.”[4]

Mikha vs. Yeshayahu: Was there a scholarly dispute regarding the revolt?

It is extremely surprising to discover a profound and significant discrepancy, between the two major prophets at the time of Chizkiyahu, regarding how Yehuda should address the danger of an Assyrian siege on Jerusalem. We cannot know with certainty when each of their prophecies was uttered, but the impression they give is of two concurrent prophecies that are directly opposed to one another – the prophetic version of a scholarly “machkloket” in the beit midrash.

In contrast to the venerable Yeshayahu with his eminent lineage, there was a prophet from the lowlands of Yehuda, named Mikha of Morasha.[5] Yeshayahu emphasized the need to turn inward, to keep away from war, and to trust in God, Who would undoubtedly strike Assyria “with the sword not of man”[6] as he did when freeing Israel from Egypt. Mikha, on the other hand, declared a need for the nation to fortify itself for war and to become a determined, aggressive army that would defeat the enemy with a mortal sword, with “seven shepherds and eight princes of men” that would lay waste to the land of Assyria “with the sword” if its soldiers dared to step foot within the borders (Mikha 5:4-5).

The entire beit midrash, as it were, was split into two opposing camps. As each new prophecy emerged from Yeshayahu, an opposite message issued from Mikha. Yeshayahu (26:20) held that everyone should take refuge in shelters and wait for the storm to pass, while God would strike the enemy with His great, sharp, powerful sword. Mikha (4:10-13) maintained that the proper strategy was to break through the enemy’s borders and strike deep in their territory: “Arise and thresh, daughter of Tzion, for I will make your horn iron, and I will make your hoofs brass, and you shall beat in pieces many peoples….” Yeshayahu declared that only God’s hand would act; Mikha insisted that the people themselves would strike the enemy with their swords, just like the sword of David the warrior (Mikha 5:1). Yeshayahu portrayed the “daughter of Tzion” as a birthing mother who has no strength left (26:17-18), while Mikha (4:10) called upon her to push “like a woman in travail” so that the fetus (the redemptive victory) could emerge.[7]

Mikha issued a call (4:8 – 5:1) to build walls, to press on and fight, and to defeat the enemy with the “sword of man,” while the terrible reality from which the nation needed to be extricated was still described in terms of “now.” Against that, he called to “the daughter of Tzion”:

And you, Migdal-Eder, the wall of the daughter of Tzion – to you shall it come; the former dominion shall come, the kingdom of the daughter of Jerusalem.

Now, why do you cry out aloud? Is there no King in you? Is your Counselor perished, that terror has overcome you like a woman in travail?

Be in pain, and labor to bring forth, O daughter of Tzion, like a woman in travail; for now you shall go forth out of the city [Jerusalem], and shall dwell in the [battle-?] field, and shall come all the way to [the army of?] Babylon; there you shall be rescued; there the Lord shall redeem you from the hand of your enemies.

And now many nations are assembled against you, that say: Let her be defiled, and let your eye gaze upon Tzion.

But they do not know the thoughts of the Lord, nor do they understand His counsel, for He has gathered them like the sheaves to the threshing floor.

Arise and thresh, O daughter of Tzion, for I will make Your horn iron, and I will make your hoofs brass, and you shall beat in pieces many peoples [...]

Now you shall gather yourself in troops, O daughter of Tzion; they have laid siege against us, they smite the judge of Israel with a rod upon the cheek.

But you, [savior from] Beit-Lechem Efrata, who are little to be among the thousands of Yehuda – out of you shall one come forth for Me who is to be ruler in Israel, whose goings forth are from of old, from ancient days [a warrior like David]. (Mikha 4:8-5:1)

Yeshayahu’s message was that the proper course of action was to turn inward, to stay away from war, and to trust in God to strike Assyria. He foretold that King Mashiach – the “shoot out of the stock of Yishai”[8] – will likewise judge the land “with the rod of his mouth,” without military might.

Mikha, in contrast, said about the savior from “Beit-Lechem Efrata”:

And he shall stand and shall lead in the strength of the Lord, in the majesty of the Name of the Lord his God, and they shall abide, for then he shall be great unto the ends of the earth.

And this shall be peace [after the victory]: when the Assyrian shall come into our land, […] we shall raise him against seven shepherds and eight princes among men.

And they shall lay waste to the land of Assyria with the sword, […]

and he shall deliver us from the Assyrian when he comes into our land and when he treads within our border. (Mikha 5:3-5)

If indeed both prophets were active in Jerusalem at the same time, we can imagine how perplexing the situation was – especially for Chizkiyahu and his ministers. As we have already seen, the text notes that Chizkiyahu paid close attention to both Yeshayahu’s and Mikha’s prophecies.

What then, was Chizkiyahu to do? Would he follow the guidance of Yeshayahu, his teacher, or the direction of Mikha, who held David and his sword as a model for emulation – the same ideal that Chizkiyahu himself was inclined to pursue?

Still, there is something that Mikha never mentions. He never utters anything resembling the idea of an alliance with Egypt. He speaks (5:7) of “the remnant of Yaakov among the nations… like a lion among the beasts of the forest, as a young lion among the flocks of sheep, which, if he goes through, treads down and tears in pieces, and there is none to deliver.” Chizkiyahu did not view Yehuda as a lion vis-à-vis Assyria, and he turned to Egypt for help. Yeshayahu protested this move with all his might, and there was no voice in the prophetic beit midrash that contested him in this regard.

Yeshayahu’s prophecies against the alliance with Egypt (Yeshayahu 30-31)

Yeshayahu trembled to see all the preparations for the revolt. Long before, during the time of Sargon, he had gone “naked and barefoot,” as he described it, to protest against any support for the rebellions originating in Ashdod, and had vehemently opposed displaying the emergency stores of Yehuda to the visiting Babylonian delegation. Now, too, after Sargon’s death, the prophet maintained his intense opposition to all this activity. The gap between himself and King Chizkiyahu, whom he had guided and abetted for so long, grew deeper, and the prophet issued an explicit call against partnering with Egypt. Let us pay close attention to part of his message:

Woe, rebellious children, says the Lord, who take counsel, but not of Me, and that form projects, but not of My spirit, that they may add sin to sin;

That walk to go down to Egypt, and have not asked at My mouth, to take refuge in the stronghold of Pharaoh, and to take shelter in the shadow of Egypt! (Yeshayahu 30:1-2)

The kingdom of Yehuda was pervaded with a sense of general mobilization. Convoys were moving toward the south, to Philistia and the border of Egypt, and delegations were traveling to Egypt to ensure that the Egyptian army would help to halt the Assyrian forces. Yeshayahu described this southward-bound traffic with great bitterness, as the conceptual inverse of the Exodus from Egypt:

The burden of the beasts of the south, through the land of trouble and anguish, from whence came the lioness and the lion, the viper and flying serpent, they carry their riches upon the shoulders of young asses, and their treasures upon the humps of camels, to a people that shall not profit them.

For Egypt helps in vain, and to no purpose; therefore I have called her arrogance that sits still.

Now go, write it before them on a tablet, and inscribe it in a book, that it may be for the time to come for ever and ever. (Yeshayahu 30:6-8)

Who was listening to the prophet while all the intensive war preparations were underway? Who would be willing to stop and listen to a sworn opponent of the kingdom’s foreign and security policy? The prophet himself provides the answer:

For it is a rebellious people, lying children; children who refuse to hear the teaching of the Lord;

Who say to the seers, “See not,” and to the prophets, “Do not prophesy for us things that are right; speak to us smooth things, prophesy delusions.

Get out of the way, turn aside out of the path; cause the Holy One of Israel to cease from before us.” (Ibid. 9-11)

These verses describe a leadership focused on energetic activity, averting its eyes from whoever foretells disaster. They are too busy to stop and listen to criticism. The voice of the prophet is silenced.

Yeshayahu returned to the “same old” prophecy that he gave to Achaz and his rebellious opponents who supported Retzin and Pekach thirty years previously. In both instances, he told the king to refrain from flattery but also to avoid any demonstration of aggression against the empire that God had permitted to dominate the region for a certain period of time. The kingdom of Yehuda would be saved only through its reliance on its slow-flowing “waters of Shiloach.” But no one listened to the prophet, and his prophecy concludes in total despair:

For thus says the Lord God, the Holy One of Israel: In sitting still and rest you shall be saved; in quietness and in confidence shall be your strength – but you refused.

For you said, “No, for we will flee upon horses” – therefore you shall flee – and “We will ride upon the swift” – therefore they that pursue you shall be swift. (Ibid. 15-16)

However, even within this image of defeat and flight that Yeshayahu described in the days of Sancheriv, he still foresaw an image of the remnant that would be saved:

And therefore the Lord will wait, that He may be gracious towards you, and therefore He will be exalted, that He may have compassion upon you, for the Lord is a God of justice; happy are all who wait for Him. (Ibid. 18)

Here, Yeshayahu is again transported to his prophetic utopia. He visualizes a future that is characterized not only by world peace, but a veritable recreation of the world – without false gods, with an abundance of blessing, a new life in which all of existence would radiate with a new light:

And the light of the moon shall be as the light of the sun, and the light of the sun shall be sevenfold, as the light of the seven days, on the day that the Lord binds up the bruise of His people and heals the stroke of their wound. (Ibid. 26)

The next prophecy (Chapter 31) is also directed against the military alliance relying on Egypt, and once again we are confronted with the contrast between reliance on the army of a mortal king and reliance on the King of the universe, and between the Exodus from Egypt and a return to Pharaoh and all that Egypt symbolizes:

Woe to them who go down to Egypt for help, and rely on horses, and trust in chariots, because they are many, and in horsemen, because they are exceedingly mighty, but who do not look to the Holy One of Israel, nor seek the Lord!

Yet He also is wise, and brings evil and does not call back His words, but will arise against the house of the evil-doers, and against the help of those who work iniquity.

The Egyptians are men, and not God, and their horses are flesh and not spirit, so when the Lord stretches out His hand, both he that helps shall stumble, and he that is helped shall fall, and they shall all perish together.

For thus says the Lord to me: Just as the lion, or the young lion, growling over its prey – though a multitude of shepherds be called forth against it, it will not be dismayed at their voice, nor abase itself for their noise, so the Lord of hosts will come down to fight upon Mount Tzion, and upon its hill.

As birds hovering, so will the Lord of hosts protect Jerusalem. He will deliver it as He protects it; He will rescue it as He passes over.

Turn to Him against Whom you have deeply rebelled, O children of Israel.

For on that day, every man shall cast away his idols of silver and his idols of gold, which your own hands have made for you, for a sin.

Then Assyria shall fall with the sword not of man, and the sword not of man shall devour him, and he shall flee from the sword and his young men shall become tributary.

And his rock shall pass away by reason of terror, and his princes shall be dismayed at the ensign, says the Lord, Whose fire is in Tzion, and His furnace in Jerusalem. (31:1-9)

Here Yeshayahu recaps the essence of his prophecy from so long ago. A focus on inner repair, justice, and righteousness, obeying God and following His commands – these are the elements of man’s only purpose in the world. It is not that Yeshayahu is in favor of or against specific political moves; he simply advocates a complete withdrawal from the international game. His vision for Yehuda and its king is one of Divine peace prevailing among all of humankind. Jerusalem should be the exemplar of this peace and should constantly strive for morality. While other kingdoms challenge and provoke one another, Yeshayahu maintains that Chizkiyahu should concern himself with his own nation and its capital city.

Appendix: The Shiloach Inscription

The image is taken from the Wikipedia site, and is allowed for publication given the proper credit.

Tamar Hayardeni from Hebrew Wikipedia

https://he.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D7%9B%D7%AA%D7%95%D7%91%D7%AA_%D7%94%D7%A9%D7%99%D7%9C%D7%95%D7%97#/media/File:Shiloach.jpg

Translated by Kaeren Fish

[1] Sancheriv’s inscription, second column, lines 73-78, in M. Kogan, Asufat Ketovot, pp. 78-79.

[2] Olam Ha-Tanakh offers the explanation that “written by name” refers to a census initiated by Chizkiyahu. The commentators avoid discussion of this episode. B. Mazar, “Masa Sancheriv le-Eretz Yehuda,” in Y. Liever, Historia Tzeva’it shel Eretz Yisrael, proposes that these verses be viewed as Chizkiyahu’s census and military recruitment lists.

[3] See the picture in the appendix to the shiur.

[4] For more about the tunnel and its convoluted route, see my article, “Ve-lo Yoreh Sham Chetz,” Al Atar 11 (Tevet 5763), pp. 29-43.

[5] See the discussion by S. Vargon, Sefer Mikha, in the Mikra le-Yisrael series, Ramat Gan 5754, pp. 11-12.

[6] Yeshayahu 31:8.

[7] The second appendix to Yeshayahu – ke-Tzipporim Afot is devoted to a description of this fundamental difference of perspective from biblical times up until Jewish political philosophy.

[8] Yeshayahu 11:1-10.

This website is constantly being improved. We would appreciate hearing from you. Questions and comments on the classes are welcome, as is help in tagging, categorizing, and creating brief summaries of the classes. Thank you for being part of the Torat Har Etzion community!